In India, the top 10 per cent take away around 42.7 per cent of the total wages, whereas the share of the bottom 50 per cent is only 17.1 per cent.

While inequality in salary is inevitable, it is also said that an excessive inequality is bad for economic growth and for the social fabric of a country. It has an adverse effect on economic growth as it brings down consumption demand. It is also more difficult to eliminate poverty in highly unequal societies.

In India, this salary gap is better than many other countries but also worse than many more. As per the International Labour Organisation (ILO) report, in India, the top 10 per cent take away around 42.7 per cent of the total wages, whereas the share of the bottom 50 per cent is only 17.1 per cent of all wages paid out.

In South Africa, the wage gap is even wider — the top 10 per cent take away 49.2 per cent of the total wages while the share of bottom 50 is 11.9 per cent.

A university degree does not necessarily guarantee a highly paid job. In Russia, there are a surprisingly high proportion of university graduates among lower-paid workers.

On the contrary, in China, the top one per cent wage earners have a higher percentage of people with an education below university or high-school level.In advanced economies, such as Europe, the highest-paid 10 per cent receive, on an average, 25.5 per cent of the total wages paid to all employees in their respective countries, which is almost as much as what the lowest-paid 50 per cent earn (29.1 per cent).

In the most recent years, many countries have adopted or strengthened minimum wages, as one way of supporting low-paid workers and reducing wage inequality. However, it is also a fact that during recent decades wage inequality has increased in many countries around the world.

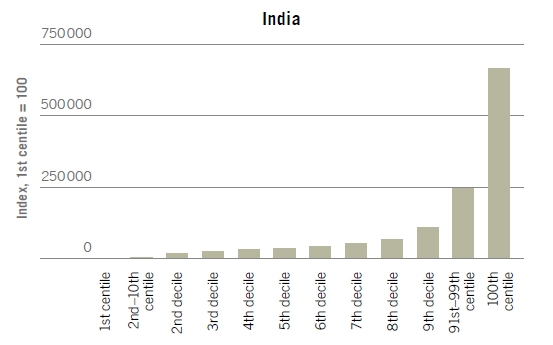

The ILO report states that in all countries, wages increase fairly gradually except in the top 10 per cent, and especially the top 1 per cent, where they jump sharply and dramatically.

If we further segregate the data, it’s seen that in Europe, the top 1 per cent earn, on an average, wages that are about eight times higher than those of the lowest 10 per cent, with multiples ranging from four in the Nordic countries to 14 in Romania.

In Vietnam, the difference is 15 times and for India, it is 33 times.

However, it doesn’t establish that better skills or higher education ensures better wages.There is also a strong co-relation between the wage gap and other demographics, such as gender, occupation, size of enterprise, nature of contract, and the economic sector.

In both developed and developing countries a university degree does not necessarily guarantee a highly paid job. For instance, in Russia, there are a surprisingly high proportion of university graduates among lower-paid workers. On the contrary, in China, the top one per cent wage earners have a higher percentage of people with an education below university or high-school level.

In both developed and developing countries a university degree does not necessarily guarantee a highly paid job. For instance, in Russia, there are a surprisingly high proportion of university graduates among lower-paid workers. On the contrary, in China, the top one per cent wage earners have a higher percentage of people with an education below university or high-school level.

Likewise, the proportion of women continuously declines as one moves towards the higher paid deciles.

In Europe, women make up 50–60 per cent of workers in the three lowest pay deciles; this share falls to about 35 per cent among the best-paid 10 per cent of employees, and further to 20 per cent among the highest-paid one per cent of employees.

In some emerging and developing countries, the contrast is even greater. For instance, the proportion of women in India in the bottom two deciles is similar to that in Europe (about 60 per cent), but drops precipitously thereafter, and in the upper half of the distribution women represent no more than 10–15 per cent of wage earners.

In the Russian Federation, women make up about 70 per cent of workers in lower deciles and this share shrinks to about 40 per cent in the upper deciles.

In terms of education, the upper deciles include a higher share of university graduates than lower deciles in all the countries sampled, but this pattern is particularly noticeable in South Africa and Argentina.

Looking at occupation and economic sector, the real-estate and financial sectors are over-represented globally among the top-paid workers as it is in Europe and, unsurprisingly, a majority of the top-paid workers occupy managerial and professional positions. In Chile, private services and trade are the largest employers of workers in the lower-wage deciles, while in Vietnam, workers in the lower deciles are much more likely to be employed in the manufacturing or social services sectors than is the case in either Europe or Chile.

However, what’s satisfactory is that India has had a decent growth in wages in the last decade – the second best among developing G20 countries and second only to China.

However, what’s satisfactory is that India has had a decent growth in wages in the last decade – the second best among developing G20 countries and second only to China.

The average wages more than doubled in China during this period and it increased by about 60 per cent in India and by between 20 and 40 per cent in most other countries in this group. The only country to witness a decline in real wages is Mexico.

(ILO ranks salaried workers in ascending order of their wages and divides them into ten groups [deciles] or 100 groups [centiles])