Somewhere between ambition and execution lies a chasm that is swallowing corporate HR’s AI investments whole. Nearly nine in ten organisations (88 per cent) expect to increase spending on artificial intelligence over the next 12 months, with more than half planning significant investment. Yet, when asked how far they have progressed, 51 per cent admit they remain stuck in the exploratory phase—assessing use cases, running pilots, building foundational understanding.

Only 5 per cent report using AI for strategic advantage. A mere 3 per cent describe it as central to their competitive strategy.

This is not cautious experimentation. It is expensive stagnation.

Avature’s AI Impact Survey, drawn from 180 HR and talent acquisition professionals worldwide, reveals an uncomfortable truth: organisations are treating AI less as a transformative technology and more as an obligation—something to be seen investing in rather than actually deploying at scale. The result is corporate theatre where investment signals commitment but delivers little beyond incremental efficiency gains.

The capability gap

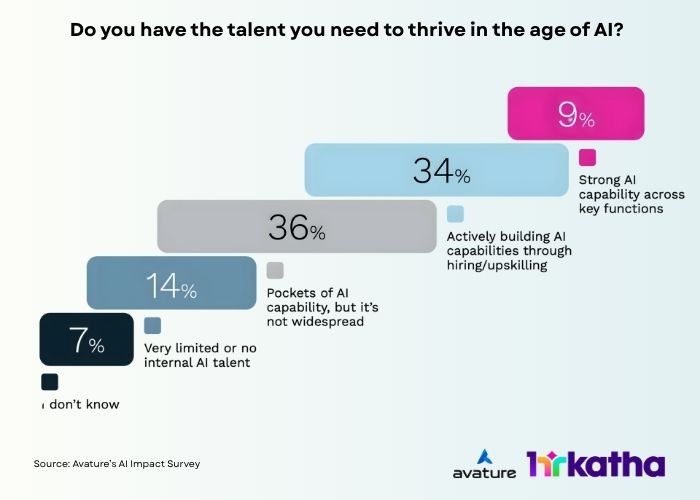

The explanation lies not in the technology but in the organisations attempting to wield it. Only 9 per cent report having strong, organisation-wide AI expertise. Seventy per cent are still building foundational skills or have mere pockets of capability. This mismatch between spending and readiness is a structural bottleneck.

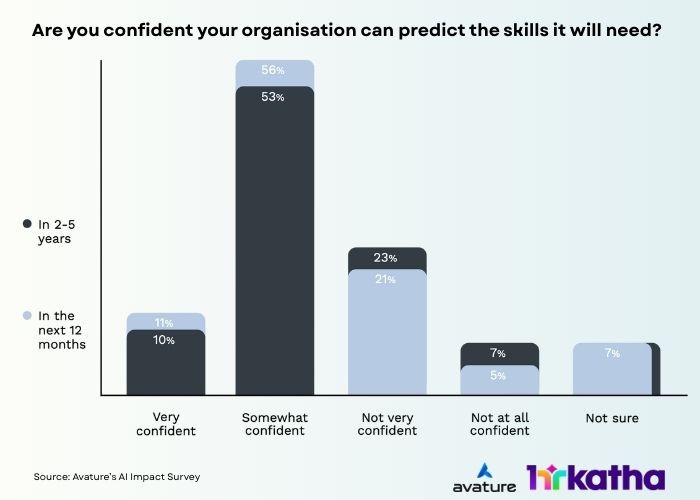

Nearly half (48 per cent) identify skills shortages as their top HR challenge, yet only 11 per cent feel “very confident” predicting skill requirements 12 months out. Without clarity on what capabilities will matter most, organisations struggle to build the workforce that AI transformation demands.

The contradiction deepens when examining deployment. Seventy per cent trust AI to answer candidate FAQs. Sixty-four per cent trust it to match candidates to roles. Useful tasks, but hardly competitive advantage.

Trust collapses when decisions require judgment. Only 34 per cent would trust AI to generate rejection letters. Nine per cent would allow it to conduct first-round interviews with decision-making power. Eight per cent would trust it to make hiring decisions autonomously. Organisations are investing heavily in a technology they fundamentally do not trust to do anything important.

The trust cliff

Only 2 per cent completely trust generative AI to make people-related decisions. Most express limited confidence: 40 per cent trust it only slightly, 28 per cent moderately, whilst 26 per cent do not trust it at all. This reflects legitimate concerns about bias and high stakes, but it also means deployment remains cautious and confined to the margins.

Regional variations add texture. Respondents in Europe, the Middle East and Africa prove significantly more willing to trust AI for candidate ranking (64 per cent) and first-round interviews (18 per cent) than their North American counterparts (41 per cent and 4 per cent).

The infrastructure problem compounds this. Twenty-eight per cent cite legacy software limitations as a top challenge. Without modern systems supporting clean data flow, AI cannot embed into processes that deliver measurable impact. This helps explain why 51 per cent remain stuck exploring whilst only 11 per cent have integrated AI into core operations.

The entry-level squeeze

Meanwhile, consequences are emerging that few organisations appear prepared to manage. Among respondents concerned about AI’s impact on early-career positions, 76 per cent believe it will significantly reduce entry-level hiring.

Entry-level roles have traditionally served as proving grounds where future leaders build context and judgment. Hollow out that layer and you may gain short-term efficiency whilst weakening future leadership. The top concern? Long-term impact on leadership pipelines (30 per cent), followed by loss of institutional knowledge transfer (15 per cent).

If this trend plays out broadly, fewer entry points mean a shrinking talent pool and more expensive external hires. Thirty-three per cent already cite workforce planning as a top priority, yet few have connected that to the disappearing entry-level tier.

The productivity paradox

Then there is what workers themselves experience. Forty-two per cent say they feel excited by AI’s potential. Yet only 24 per cent report that AI genuinely helps them reclaim time for thinking, rest or life outside work. For 45 per cent, any time saved is quickly absorbed by additional responsibilities.

When asked how AI makes them feel, “excited” and “hopeful” appear alongside “nervous”, “skeptical” and “overwhelmed”. The balance is precarious.

The innovation mirage

Where, then, is the strategic value organisations claim to be chasing? At present, AI’s most substantial returns concentrate in day-to-day execution: boosting productivity (67 per cent), improving user experiences (40 per cent) and supporting better decision-making (36 per cent). Only 27 per cent say AI is driving innovation today. Just 7 per cent report it is contributing to entirely new business models.

Optimism for the future runs higher. Looking two to five years ahead, 38 per cent anticipate AI will drive innovation. Fifteen per cent expect it to create new business models—more than double today’s figures. Expectations for revenue growth triple, from 5 per cent now to 14 per cent in the near term.

Yet this optimism must be weighed against current reality. If organisations struggle to deploy AI effectively for straightforward tasks like scheduling interviews—where trust and capability gaps are manageable—what basis exists for confidence that they will suddenly master business model innovation?

Creative stagnation

Joseph Schumpeter understood that capitalism progresses through creative destruction—old structures swept away by new ones. What we are witnessing in corporate HR is something closer to creative stagnation: new technology deployed in ways that preserve rather than challenge existing structures, delivering marginal improvements whilst avoiding fundamental change.

The 88 per cent increasing investment represent not a wave of transformation but a collective hedge. No one wants to be caught behind if AI proves transformative. Yet few are willing to make the organisational changes—in governance, architecture, capability and culture—that would allow AI to actually transform anything.

The 5 per cent using AI strategically have solved problems the other 95 per cent have not. They have built trust through transparency. They have invested in interoperable infrastructure rather than accumulating point solutions. They have developed organisation-wide capability rather than relying on pockets of expertise. They have redesigned processes, not just automated existing ones.

The rest remain caught between knowing what they should do and lacking conviction to do it. Pilots proliferate. Use cases multiply. PowerPoint decks celebrate progress. Yet the core processes that define talent strategy—how organisations attract, assess, develop and deploy people—remain largely untouched.

The divide between those 5 per cent and everyone else will likely widen before it narrows. First-mover advantages compound in AI deployment. Organisations that develop genuine capability early will attract better talent, make better decisions faster and build data advantages that become self-reinforcing.

The solution is not more investment in AI tools. It is investment in the foundations that make AI useful: modern architecture, clean data, organisation-wide capability, transparent governance and—most critically—the courage to deploy AI where it might actually matter rather than confining it to tasks that do not.

Until that happens, the gap between the 88 per cent investing and the 5 per cent succeeding will stand as a monument to corporate risk aversion and the high cost of mistaking activity for progress. The question facing HR leaders is not whether to invest in AI—that decision has been made. The question is whether to invest in becoming organisations capable of using it. On that question, the data suggests, most have yet to offer a convincing answer.