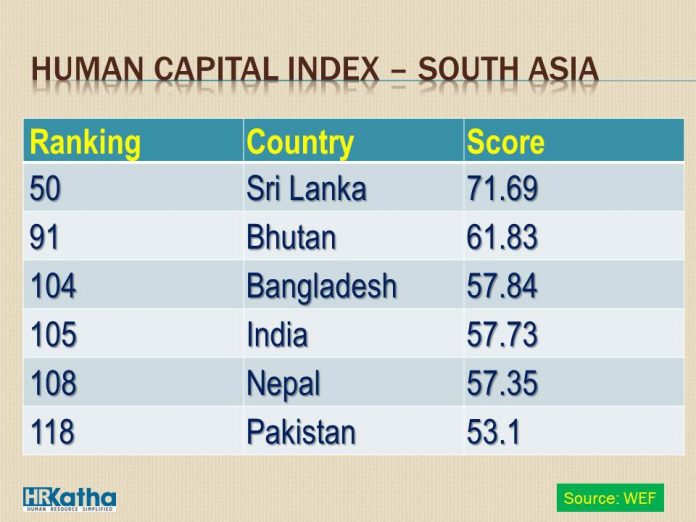

According to Human Capital Report released by World Economic Forum 2016, on June 28, India ranks at the top of the bottom quartile of the Index – 105 of 130 countries.

Ranked at 105 in Human Capital Index (HCI) by World Economic Forum, India with a score of 57.73 is at the top of the bottom quartile of the pyramid.

The WEF report for 2016, which ranks 130 countries on how well they are developing and deploying their human capital, focusing on education, skills and employment, was released on June 28.

Last year, India was ranked at No. 100 among 124 countries with a score of 57.62. So in terms of overall score, India has maintained a status quo, though its rank has dropped by 5 positions.

In the South Asian region, India is way behind Sri Lanka and Bhutan, almost at par with Bangladesh, but ahead of Nepal and Pakistan.

Sri Lanka with an overall score of 71.69 is ranked at No. 50, while Bhutan holds the No. 91 position with an overall score of 61.83. Bangladesh, with a score of 57.84, is one notch above India.

Although India’s educational attainment has improved markedly over the different age groups, its youth literacy rate is still only 90 per cent which is ranked 103rd globally and way behind other emerging markets.

Besides, India also ranks poorly on labour force participation and employment gender gap – ranked 121 among 130 countries.

The three most populous countries of South Asia — Bangladesh, India and Pakistan are held back in terms of employability – for similar reasons.

These three countries lag behind due to insufficient educational enrolment rates and poor-quality primary schools. The youth literacy rate in the three countries stands at 83 per cent, 89 per cent and 75 per cent, respectively.

The educational performance of these three countries is somewhat better at the tertiary level, despite rather low levels of skill diversity among their university graduates.

This implies a strong specialisation in a limited number of academic subjects. All three countries also exhibit significant employment gender gaps, worsening the difficulty of finding skilled employees.

However, in terms of ease of finding skilled employees, India’s performance, with a score of 55.71, is not so bad – it is ranked at No. 45. In comparison, Bangladesh with a score of 43.44 and Pakistan with score of 44.05 is ranked at No. 97 and No. 93, respectively.

The other two parameters, on which, India scores high is quality of education system (53.24) and staff training (53.08).

On the other hand, Sri Lanka, which is ranked 50 among 130 countries, benefits from strong educational enrolment and basic education completion rates as well as positive perceptions of the quality of its primary schools and education system overall – ranked 23rd on both these parameters. However, it underperforms when it comes to translating the potential of its young population to the workforce, with one in four young people not active in employment, education or training.

China, in comparison, with a score of 67.81, ranks in the mid-range of the overall Index scores – well ahead of the other BRICS nations except for the Russian Federation. Its younger population fares significantly better than its 55–64 and 65 and over age groups as a result of increasing educational attainment in the population. It also scores comparatively well on the Ease of finding skilled employees (39th), Vocational enrolment (29th) and Economic complexity (18th) indicators, setting the country up well for the future.

The World Economic Forum suggests that employers and employees need to start thinking about skill bundles, not job titles. While employees and employers often rely on academic degrees and previous job titles to determine fitness for a new role, a key finding in the report reveals that job titles can mean different things in different industries and geographies.

The higher the skills overlap between two industries, the easier it is to transfer between them. For instance, there is little skills overlap between LinkedIn members with the job title ‘data analyst’ in the market research and oil & energy industries. By contrast, data analysts in the financial services and consumer retail industries exhibit very similar skills.

Besides, it suggests that re-skilling may be easier than we thought. It believes that taking a focus on skills rather than jobs may broaden the talent pool for employers – and create new opportunities for workers.

For instance, only about 84,000 of LinkedIn’s 430 million members have the job titles ‘Data Scientist’ or ‘Data Analyst’, a highly in-demand profession for which many employers report shortages.

However, analysis of the skills reveals an additional 9.7 million members that possess one or more of the primary or sub-skills for Data Scientist and Data Analyst, among which 600,000 have at least five of these skills. While this clearly does not make them data scientists, data such as this provides a wider range of options for developing new talent through a relatively modest amount of supplemental training.

Value our content... contribute towards our growth. Even a small contribution a month would be of great help for us.

Since eight years, we have been serving the industry through daily news and stories. Our content is free for all and we plan to keep it that way.

Support HRKatha. Pay Here (All it takes is a minute)

The fact that India has fallen down by four notches over last year’s rating seems to be a matter of serious concern. While in terms of ease of getting skilled workforce, India seem to have performed better, there remains a great deal to be done as the percentage of skill trained and certified workforce in India is significantly lower than the neighborhood countries like China and South Korea.

All in all, good information, surely meant to be acted upon.